Washington Books

Washington Books

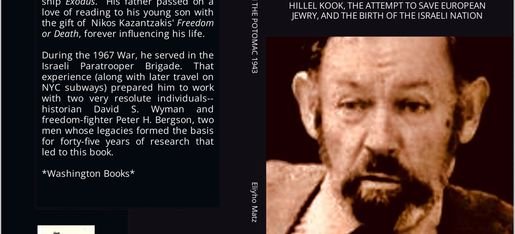

By Eliyho Matz

Finally we got the whole story: Americans hate Jews and others. The nation’s mood has not changed, the past is the present, the present is the past.

This according to Ken Burns.

The Mongols being Mongols, and not really knowing how to write or read, found qualified people to write “The Secret History of the Mongols.” The people who wrote the history were of Chinese and Iranian descent and, not to be surprised, they glorified Genghis Khan. So in America we got Ken Burns. The job he was given was, simply, tell a story and make sure that FD Roosevelt looks, appears, and is presented in such a way, that all who see the doc will be happy that we had such a President. Sympathy should be aroused for the President — even though from a historian’s point of view, it is not needed or necessary. Roosevelt was a great President. How great? Well, he pulled the nation together when the nation was in dire trouble.

But then, the title of the documentary is called “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” and what does that mean? Well, what it does not mean is what Ken Burns did with it, interviewing individuals who tell us personal memories about themselves or their families!

The Holocaust is a much larger issue: how did it come to be that there was the massacre of almost the entire body of Jewry in Europe? — that is the meaning of the Holocaust.

And why did the Germans decide to kill the Jews? Does anybody have an answer?

I do have one, but I am not going into it here. In his doc Burns presents footage that we have seen before and probably will see again.

So if she or he asks, “What did the world do to stop the killing?” Well, that should be what we really should ask. Is the question a real question? Or is it a non-question?

To me personally, that was always the question. Ken Burns, not being a historian, but rather a bad collector of film footage, and worst of all, associating or engaging himself with some bad dudes whose historical perspectives are twisted, presented us with a fairytale of the first class quality of fairytales.

OK, finally Roosevelt under pressure is announcing the creation of a War Refugee Board. Pay attention to the word “Refugee” — Hitler was not killing “Refugees,”

Hitler was killing Jews, so how come the American response was using the wrong words to describe the massacre? Using Mongol tricks.

As recorded in a Congressional hearing at the end of 1943, Peter Bergson protested that use of the word “Refugee,” and suggested unless someone does something to save European Jews, we might as well call them “potential corpses!” Ken Burns, I guess, didn’t have time to look at the Congressional hearing.

In any case, what is more historically important is to explain Roosevelt’s actions and behavior from the moment he tells the Jewish leadership the fact that he has the knowledge about the European situation. By the way, Burns tells us about the meeting but fails to tell that it was the only time in the war that the President met with such a delegation!!!

Now, America’s response to the Holocaust is rather an important historical issue that Burns has preferred not exactly to tell us.

His story about Bergson is categorically wrong! His story about the formation of the War Refugee Board is wrong! Morgenthau, the distinguished American Jew, was not behind it, and it was not even Pehle, who eventually ran this Board.

The creation of the War Refugee Board was the work of Bergson, Will Rogers, Jr., and Josiah E. Dubois, a lawyer at the Treasury. It was Bergson who worked very closely with them. Elbert Thomas and Guy Gillette, Bergson’s friends in the Senate, did their job, too; without their help too, Roosevelt would not have reacted!

Is an American college student better off in his or her understanding of the Holocaust after seeing Burns’ Holocaust fiasco? I doubt it. Ken Burns can twist and manipulate images, he can record individuals telling stories, but that will not hold for a long time.

History always plays tricks; someday someone will have to explain why for the entire year 1943 the American nation failed to stand up to one of the most horrific massacres in history.

For further reference, please see my short book “Auschwitz on the Potomac” for a start.

Also, freely available till Oct. 7, 2022, is a film by Pierre Sauvage, “Not Idly By—Peter Bergson, America and the Holocaust.” In addition, there is the film by Laurence Jarvik, “Who Shall Live and Who Die.“

Eliyho Matz worked as Peter Bergson’s assistant for ten years. He is the author of “Auschwitz on the Potomac 1943: Hillel Kook, the Attempt to Save European Jewry and The Birth of the Israeli Nation” (2022) and “Who is an Israeli?” (2012)

Two Gentiles,Two Jews and Roosevelt: A Response to Ken Burns

The author of AUSCHWITZ ON THE POTOMAC 1943 differs with Ken Burns' conclusions as presented in his PBS series...

Destiny of the Chosen People

Peter Miller, a printmaker living in Kamakura, Japan, reviews Eliyho Matz's AUSCHWITZ ON THE POTOMAC 1943...

Peter Miller's Substack: https://peterdanielmiller.substack.com/p/hearts-and-minds

I met the author of this remarkable book forty years ago, as a result of making Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die? -- my documentary film about Peter Bergson (the pen name of Hillel Kook) and his struggle to persuade America to stop the Nazi extermination of European Jewry during World War II. Eliyho Matz was then a young man, pursuing academic study, publishing journal articles, who had been a research assistant for Professor David Wyman, author of The Abandonment of the Jews, while a graduate student in history at the Unversity of Massachussetts, publishing research in intellectual journals like Midstream. He also worked for Bergson, assisting him to define the Israeli national identity, which became subject of Matz's earlier publication, Who is an Israeli?

Like Bergson, Matz found himself subject to the fate of an outsider thought too critical of the Establishment, and left academia to work in the private sector. However, he contintued to research and analyze the causes and consequences of the tragic fate of European Jewry during World War II, America's failure to act decisively, and the prophetic role of Peter Bergson, Ben Hecht, Will Rogers, Jr., members and supporters of the Emergency Committee for the Rescue of the Jewish People of Europe and its successor organization, the Hebrew Committee for National Liberation.

The results of Matz's years of research and contemplation may be found in this book. Most significantly, working as a researcher for Wyman and Bergson, Matz scoured the key historial archives related to America and what has come to be known as "The Holocaust." He kept his own copies of historical documents that are to be found in reproduced in the chapters and appendices of this book--documents providing evidence for Matz's contention that Peter Bergson's actions from 1942 through the end of 1943 "comprise the most important events in the history of Jews worldwide, as well as a very important event in American history.”

Matz makes a convincing case that Bergson's activities led to the rescue of thousands of European Jews through the work of the War Refugee Board as well as to the establishment of the State of Israel following the war. His interviews with Bergson give some sense of is approach to the issue of identity, which Bergson held as the key to understanding both the Nazi extermination campaign during World War II and Israeli nationalism in the aftermath.

That is to say, if Americans, American Jewish leaders, and Israelis had listened to what Peter Bergson had to say instead of fighting him--he was subject to attacks by The Washington Post, FBI investigation, and attempts at deportation by the US Government, as well as continuous criticism from American Jewish leaders--there was an excellent chance that the Nazi extermination program could have been stopped by the Allies in 1943. Bergson's recommended policies might have saved millions more from tragic deaths, as well as establishing the new nation of Israel in a more positive demographic and political environment.

Eliyho Matz has done the world a service by bringing this documentary history together in book form, so that readers may see for themselves what was known, documented, and reported about the Holocaust during the 1940s, and hopefully be able to apply his information and analysis to the thorny problems facing America, Israel and the world today.

--Laurence Jarvik, August 2022, Clearwater, Florida

Interview with Eliyho Matz posted on YouTube in 2011

The American Way of Empire:

How America Won a World—But Lost Her Way

by james kurth

washington books, 464 pages, $30

The Cold War ended with a historical irony: The communists who were convinced they had history on their side ended up losing. The U.S. and its E.U. and Pacific allies emerged from the Cold War with unrivaled diplomatic, cultural, and economic power, while the American military enjoyed combat primacy in all domains. Liberal democracy and American-style capitalism, undergirded by multilateral institutions, seemed the way of the future. Confident in what they imagined their limitless success, the Baby Boomers who dominated American foreign policy after 1992 invented their own philosophy of history. It is less explicit than Marxism’s dialectical materialism but often tends toward the same dogmatic confidence: America’s liberal democratic project has history on its side.

Alas, thirty years after our moment of victory, America seems strategically adrift. Authoritarian adversaries are ascendant, while many Americans feel we have squandered our victory. How did America’s Boomer elites manage to fritter away their Cold War triumph?

In The American Way of Empire, James Kurth gathers reflections that, taken together, provide an answer. His central insight is political. The health of the American social contract is ultimately the wellspring of American power and the foundation for our grand strategy.

Facing first the fascist and then the communist challenge, America was fortunate to have political elites who recognized that American power rested on the commitment of its citizens. As Kurth explains, those who crafted postwar foreign policy recognized the need to buttress the “free world.” The Marshall Plan was the first of many initiatives that linked America’s prosperity to that of its allies abroad. But our elites calculated that the sacrifice of American resources and lives would generate returns to Americans over the long haul. Global security and its economic architecture were ultimately anchored on American prosperity and cultural unity, and the resulting empire was beneficial to the U.S. in the long run.

Unlike the Soviets, who created satellites out of allies and subjects out of allied citizens, America created alliance systems, emphasizing strategic pragmatism over ideological purity. NATO and SEATO (NATO's counterpart in Asia) were pillars of this system. Our grand strategy during the Cold War gave weaker allies a remarkable degree of autonomy. This won us loyalty as America bore the military costs of sustaining security. As Kurth documents, an important carrot that kept allies in the American-led system was access to the U.S. economy. This is the unique institutional arrangement—economic as much as military—that defined what Kurth calls the American way of empire that won the Cold War.

But now America seems to have depleted its diplomatic, cultural, and economic capital. As Kurth observes, the Cold War ended with the image of the U.S. Army as “an efficient, effective, and even invincible force.” After twenty years of continuous warfare in the Middle East, that image has been replaced by one of “an incompetent, feckless, and even mindless bureaucracy that could do almost nothing right.” In perhaps the greatest indictment of post-Cold War policy elites, the descendants of the Greatest Generation voted for a candidate who swore to dismantle the global strategic architecture that their predecessors had sacrificed so much to build and sustain. How did this come about?

The end of the Cold War in America (and Europe) marked the crossing of a generational and ideological boundary. The last of the presidents of the Greatest Generation, whose lives were defined by the West’s fight against fascists and communists, handed the reins of power to a generation that had come of age looking askance at America’s role in the Cold War, inveighing against the moral cost of strategic compromise, and questioning the utility of military power.

Instead of seeing national destiny as an outcome of contingent decisions, Boomer elites believed in historical inevitability and assumed that history belonged to democracy and capitalism (an ironic echo of the defeated Marxists). They believed that the twenty-first century would be shaped by multilateral institutions and globalization. It was an expression of hope, not sober reason.

At the same time, the economic foundations of American prosperity were transformed. As Kurth observes, the Reagan-era response to the stagflation crisis of the 1970s may have buttressed the self-respect of working-class Americans, but it undermined their economic self-interest. After the end of the Cold War, the trend established after 1945 accelerated as economic elites “earned their income and made their wealth much more in the international economy than in the national economy.” Manufacturing was transferred to East Asia, so much so that “the U.S. defense industrial base is now in East Asia.”

By the 2010s, “the U.S. economic elite had repeatedly demonstrated during the past thirty years, and especially during the past ten years, that it cared nothing about the economic condition of the majority of Americans and of America itself. Rather, it had come to think about citizens in the United States in a way similar to how it has always thought about residents of Latin American countries.” By Kurth’s reckoning, the American social contract is in tatters.

This has decisive strategic consequences. Misreading the wellsprings of American strategic capacity and power in recent decades, foreign policy elites have taken the support of ordinary citizens for granted. Political elites refuse to play an arbitrating role between ordinary citizens and economic elites who push selective advantages at the cost of many. The sense of nationalism that animated civic obligations is seen as an outdated commitment to be replaced with ideals of global citizenship.

Kurth argues that after the Cold War, American resources and lives were deployed in pursuit of objectives that benefited a selective group of elites. These elites became, in turn, ardent cheerleaders for globalization, while the American military became a discount global security shop. Political elites no longer saw the need to restrain the appetites of economic elites. In fact, they became surrogates for economic elites who benefited from globalization. The pinnacle of human existence in the globalized world became a trip to Davos for the powerful and a trip to Walmart for the average American.

2016 saw an election in which tens of millions voted for someone who openly called into question the global institutions that his predecessors had sacrificed so much to build and sustain. Having been hoodwinked repeatedly in the last thirty years, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Greatest Generation found solace in their only alternative, and made common cause with a strategic nihilist. The American Way of Empire explains why we must see this populist upsurge as a democratic indictment of our policy elites; they inherited the world on a string and lost it spectacularly, and along the way they also failed the American people.

Today, America's diplomatic, cultural, and economic power is vastly diminished. Our military barely holds onto its combat primacy. And America’s citizens—the elemental source of American power—are deeply skeptical of our continued strategic profligacy.

The gravamen of The American Way of Empire is that American power depends upon a strong social contract between economic elites and the general population. We will be unable to meet the strategic challenges of the twenty-first century—China foremost among them—unless we repair that social contract and reunite the economic interests of elites with the interests of the rest of the country, as well as blunt the cultural hostility of our leadership class toward the majority of their fellow citizens. Kurth is unsparing: “The most crucial of all fractures of today is the fractured relationship between the U.S. economic elite and everyone else. And that fracture will not be repaired until that elite is removed.”

Buddhika Jayamaha is assistant professor of military and strategic studies at the United States Air Force Academy. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the United States Air Force Academy, USAF, or the DOD.

The American Way of Empire: How America Won A World—But Lost Her Way; by James Kurth; Washington Books; 464 pp., $30.00

“The most important feature of an empire,” James Kurth explains in his brilliant new book:

"…is how it seeks to order not just its own territories but an entire world, to set the standard for the way of life and for the spirit of an age. This is exemplified in the empire’s particular vision of politics, economics, culture, and ultimately of such fundamentals as human nature and the meaning of life itself. These compose its imperial idea."

In The American Way of Empire, Kurth argues the imperial idea of the Habsburg Empire emerged from the Roman Catholic faith. In contrast, Protestant Christianity imbued British imperial projects with meaning and purpose. The French, meanwhile, ordered their empire around Enlightenment principles, such as reason. As for the Nazis, their vision combined the power of the German state with racial ideology. And the Soviets promoted an economic development model rooted in Marxism.

These empires likewise each promoted an ideal human type—the men and women who sought to bring order to the world. For the Habsburgs, the imperial servant strove to be a saint. In Britain, the virtues of loyalty, honesty, integrity, common sense, and good judgment were associated with the imperial soldier and the civil administrator. The French adored the man of action in the service of reason, while the Nazis and Soviets found their ideal types in the SS officer and the new “Soviet man,” respectively.

As for the American Empire, which is the central focus of Kurth’s analytical tour d’horizon, three elements have been central to the nation’s imperial idea: peace based on military protectorates; prosperity derived from economic reconstruction; and the ubiquity of its popular culture. In America, Kurth writes, the ideal human type was once found in the middle-aged men who designed the American empire and ordered the world in the ’40s and ’50s.

In contrast with other scholars who situate the beginnings of the American Empire either in the 19th century ideal of Manifest Destiny or in the Spanish-American War, Kurth asserts that the American Empire began on the deck of the U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay at the end of World War II. He does not dismiss these earlier “cycles of American foreign policy,” he merely suggests instead that they provide strategic lessons, which, when ignored, create great tumult for the United States.

No American grand strategy, for instance, can be sustained in the absence of unity. Hence, the territorial consolidation of the West could not be fully realized until America’s sectional conflict had been resolved. American grand strategy must also respect cultural differences as well as the presence of other great powers in the world. The Caribbean was culturally distinct from the United States, and Canada an extension of the British Empire. As a result, the United States showed restraint vis-à-vis its northern neighbor and constructed a sphere of influence in the Caribbean basin.

With the end of World War II, the country entered a new cycle of foreign policy, one in which it conceived of its interests globally. Again, the consolidation of new spheres of influence without complete annexation proved the most reasonable path to world order. Consequently, Western Europe and Northeast Asia became military protectorates in order to guard against Soviet expansionism and Mao’s China. To legitimize this new American Empire, Washington reconstructed the economies of these protectorates while also opening them up to American popular culture.

As Kurth tells it, the individual men who were “Present at the Creation” of this extraordinary and unprecedented imperial structure were emblematic of the American empire’s ideal types. Each was a truly wise man, most especially George Marshall, Dean Acheson, George Kennan, and three successive presidents—Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman, and Dwight Eisenhower.

While many scholars conceive of empire in strict territorial terms, these men imagined a new American way of empire, even though they may never have used such an expression. This empire was not based purely on territory, nor was it exercised through a colonial system. Instead it relied on indirect rule, the use of alliances, spheres of influence, and international organizations to both maintain world order and spread economic prosperity.

But these ends served more lofty objectives as well. “The grand project of the American empire,” Kurth writes, “was to redefine, or even reinvent, the traditional American national interest, which preserved American values, into a new American-led global order, which promoted universal values.” With the end of the Cold War, it seemed this new world order was at hand, but the gap between a global ideology and the resistance of local realities has called the project’s aims into question.

In his book, Kurth takes direct aim at the “selfish elites” who have bungled the United States’ position in global politics, writing “they do not even think of themselves as American.” Since the 1950s, the “ideal human type of the American empire” has “become the popular entertainer or sports star.” The requisite qualities for this ideal type are “inherent talent, self-centeredness, energy, and aggressiveness.” None of these qualities, he asserts, are associated with maturity. Like the ideal types in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, they are the traits of the young, and in the case of the United States, the adolescent.

The emergence of this ideal type stems from the contradiction at the center of the American imperial ideal that our peace and prosperity produce a self-centeredness in our people, thereby undermining the entire edifice. Pax Americana “is becoming an empire of adolescents, by adolescents, and for adolescents.” But in the end, Kurth concludes, “an adolescent empire will be no empire at all.”

Kurth’s provocative and passionate prose, accompanied by his brilliant analysis, make for lively reading. Indeed, his discussion of the American imperial idea constitutes but one of the book’s many originalities. Divided into four sections, each following distinct thematic trajectories, The American Way of Empire investigates the rise and apparent decline of the American Empire from 1776 to the present. Eccentric, but replete with wisdom, the book draws on several fields: history, comparative politics, international relations, and political economy among others. Sometimes Kurth’s prognoses and conclusions alarm, but he also suggests possible methods for the nation to extract itself from its present quagmire.

In the book’s first section, devoted to ideology, Kurth contends that scholars have until recently ignored Protestantism in their assessments of American foreign policy. In what he calls a “deformation” of the Protestant faith, Kurth explains how the original Protestantism in the United States slowly passed through distinct phases and morphed into something distinct from its earlier iterations. This development, in Kurth’s view, has undermined American sovereignty.

In a second section on strategy, Kurth explains why the United States has not been able to develop a coherent grand strategy for the present global era. He places the blame for this failure on postmodernism, multiculturalism, globalization, and economic policies benefitting elites at the expense of everyone else. These trends have eliminated the most basic prerequisite for any grand strategy: unity. Imperial overextension and violations of other great powers’ spheres of influence have also aggravated the situation. Worse, the United States promotes global transformations that impede the nation’s capacity to provide global order, one of the mainstays of the empire’s legitimacy.

The third section of Kurth’s book, entitled “Insurgency,” investigates major challenges to U.S. imperial projects in the early part of the new millennium. While Kurth blames the globalist ideology and American imperialism for the rise of Islamic terrorism, he exhibits special scorn for neoconservatives, notably their inability to see the disaccord between local realities in Iraq and their dreamy-eyed visions for the country. He also writes ominously of Western immigration policies, stating that the mass migration of Muslims into Western societies “pose[s] serious problems for domestic security” in America and Europe.

Kurth’s concluding section, possibly the most outstanding of the entire work, examines the economic elites who shape American foreign policy. Here he argues that plutocracies have the ability to generate the resources and wealth necessary for a nation to become a great power. However, when they are based primarily on high finance and a multinational industrial class hell-bent on exploiting cheap foreign labor, they tend to offshore production.

Such results have not been good for the United States. Because of the resulting economic growth in other countries, poor investment decisions at home, and the internal strife between economic elites and the people who suffer on account of globalization, the United States’ relative power in the world has declined.

The American Way of Empire is an entirely original and interpretive exploration of the American imperial project from its origins in the 19th century up to the present. But the book is not without weaknesses. Because it is a series of updated articles originally published over the course of the last 30 years, the contents of the individual chapters sometimes overlap, and occasionally they do not fall perfectly into the book’s design. This shortcoming, however, has its advantages. The chapters possess stand-alone arguments that can be read individually. Moreover, all of them are highly rewarding for anyone willing to read closely.

Charles W. Sharpe Jr. is a professor at the Royal Military College of Canada.

James Kurth Interview

Press Kit for James Kurth's THE AMERICAN WAY OF EMPIRE

Click below to download a copy of the Press Kit for James Kurth's THE AMERICAN WAY OF EMPIRE...

Now On Sale

As an audibook at Audible.com:

https://www.amazon.com/American-Way-Empire-America-World-but/dp/B08BQDT3XQ/

At POLITICS & PROSE bookstore in Washington, DC...

Hardback:

https://www.politics-prose.com/book/9781733117807

Or at your local indie bookstore:

https://www.indiebound.org/book/9781733117807

or at:

https://www.amazon.com/American-Way-Empire-America-World/dp/1733117806

Paperback:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1733117822

Kindle:

https://www.amazon.com/AMERICAN-WAY-EMPIRE-America-World-But-ebook/dp/B08287CKTC

NOOK:

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-american-way-of-empire-james-kurth/1135360943?ean=9781733117838

KOBO:

https://www.kobo.com/us/en/ebook/the-american-way-of-empire

Reviews:

First Things (6/8/2021)

AMERICA ADRIFT

by Buddhika Jayamaha

6 . 8 . 21

The American Way of Empire:

How America Won a World—But Lost Her Way

by james kurth

washington books, 464 pages, $30

The Cold War ended with a historical irony: The communists who were convinced they had history on their side ended up losing. The U.S. and its E.U. and Pacific allies emerged from the Cold War with unrivaled diplomatic, cultural, and economic power, while the American military enjoyed combat primacy in all domains. Liberal democracy and American-style capitalism, undergirded by multilateral institutions, seemed the way of the future. Confident in what they imagined their limitless success, the Baby Boomers who dominated American foreign policy after 1992 invented their own philosophy of history. It is less explicit than Marxism’s dialectical materialism but often tends toward the same dogmatic confidence: America’s liberal democratic project has history on its side.

Alas, thirty years after our moment of victory, America seems strategically adrift. Authoritarian adversaries are ascendant, while many Americans feel we have squandered our victory. How did America’s Boomer elites manage to fritter away their Cold War triumph?

In The American Way of Empire, James Kurth gathers reflections that, taken together, provide an answer. His central insight is political. The health of the American social contract is ultimately the wellspring of American power and the foundation for our grand strategy.

Facing first the fascist and then the communist challenge, America was fortunate to have political elites who recognized that American power rested on the commitment of its citizens. As Kurth explains, those who crafted postwar foreign policy recognized the need to buttress the “free world.” The Marshall Plan was the first of many initiatives that linked America’s prosperity to that of its allies abroad. But our elites calculated that the sacrifice of American resources and lives would generate returns to Americans over the long haul. Global security and its economic architecture were ultimately anchored on American prosperity and cultural unity, and the resulting empire was beneficial to the U.S. in the long run.

Unlike the Soviets, who created satellites out of allies and subjects out of allied citizens, America created alliance systems, emphasizing strategic pragmatism over ideological purity. NATO and SEATO (NATO's counterpart in Asia) were pillars of this system. Our grand strategy during the Cold War gave weaker allies a remarkable degree of autonomy. This won us loyalty as America bore the military costs of sustaining security. As Kurth documents, an important carrot that kept allies in the American-led system was access to the U.S. economy. This is the unique institutional arrangement—economic as much as military—that defined what Kurth calls the American way of empire that won the Cold War.

But now America seems to have depleted its diplomatic, cultural, and economic capital. As Kurth observes, the Cold War ended with the image of the U.S. Army as “an efficient, effective, and even invincible force.” After twenty years of continuous warfare in the Middle East, that image has been replaced by one of “an incompetent, feckless, and even mindless bureaucracy that could do almost nothing right.” In perhaps the greatest indictment of post-Cold War policy elites, the descendants of the Greatest Generation voted for a candidate who swore to dismantle the global strategic architecture that their predecessors had sacrificed so much to build and sustain. How did this come about?

The end of the Cold War in America (and Europe) marked the crossing of a generational and ideological boundary. The last of the presidents of the Greatest Generation, whose lives were defined by the West’s fight against fascists and communists, handed the reins of power to a generation that had come of age looking askance at America’s role in the Cold War, inveighing against the moral cost of strategic compromise, and questioning the utility of military power.

Instead of seeing national destiny as an outcome of contingent decisions, Boomer elites believed in historical inevitability and assumed that history belonged to democracy and capitalism (an ironic echo of the defeated Marxists). They believed that the twenty-first century would be shaped by multilateral institutions and globalization. It was an expression of hope, not sober reason.

At the same time, the economic foundations of American prosperity were transformed. As Kurth observes, the Reagan-era response to the stagflation crisis of the 1970s may have buttressed the self-respect of working-class Americans, but it undermined their economic self-interest. After the end of the Cold War, the trend established after 1945 accelerated as economic elites “earned their income and made their wealth much more in the international economy than in the national economy.” Manufacturing was transferred to East Asia, so much so that “the U.S. defense industrial base is now in East Asia.”

By the 2010s, “the U.S. economic elite had repeatedly demonstrated during the past thirty years, and especially during the past ten years, that it cared nothing about the economic condition of the majority of Americans and of America itself. Rather, it had come to think about citizens in the United States in a way similar to how it has always thought about residents of Latin American countries.” By Kurth’s reckoning, the American social contract is in tatters.

This has decisive strategic consequences. Misreading the wellsprings of American strategic capacity and power in recent decades, foreign policy elites have taken the support of ordinary citizens for granted. Political elites refuse to play an arbitrating role between ordinary citizens and economic elites who push selective advantages at the cost of many. The sense of nationalism that animated civic obligations is seen as an outdated commitment to be replaced with ideals of global citizenship.

Kurth argues that after the Cold War, American resources and lives were deployed in pursuit of objectives that benefited a selective group of elites. These elites became, in turn, ardent cheerleaders for globalization, while the American military became a discount global security shop. Political elites no longer saw the need to restrain the appetites of economic elites. In fact, they became surrogates for economic elites who benefited from globalization. The pinnacle of human existence in the globalized world became a trip to Davos for the powerful and a trip to Walmart for the average American.

2016 saw an election in which tens of millions voted for someone who openly called into question the global institutions that his predecessors had sacrificed so much to build and sustain. Having been hoodwinked repeatedly in the last thirty years, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of the Greatest Generation found solace in their only alternative, and made common cause with a strategic nihilist. The American Way of Empire explains why we must see this populist upsurge as a democratic indictment of our policy elites; they inherited the world on a string and lost it spectacularly, and along the way they also failed the American people.

Today, America's diplomatic, cultural, and economic power is vastly diminished. Our military barely holds onto its combat primacy. And America’s citizens—the elemental source of American power—are deeply skeptical of our continued strategic profligacy.

The gravamen of The American Way of Empire is that American power depends upon a strong social contract between economic elites and the general population. We will be unable to meet the strategic challenges of the twenty-first century—China foremost among them—unless we repair that social contract and reunite the economic interests of elites with the interests of the rest of the country, as well as blunt the cultural hostility of our leadership class toward the majority of their fellow citizens. Kurth is unsparing: “The most crucial of all fractures of today is the fractured relationship between the U.S. economic elite and everyone else. And that fracture will not be repaired until that elite is removed.”

Buddhika Jayamaha is assistant professor of military and strategic studies at the United States Air Force Academy. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the United States Air Force Academy, USAF, or the DOD.

https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2021/06/america-adrift

Kirkus Reviews (11/29/2019):

A remarkably comprehensive account of the history of American foreign policy, coupled with unflinching predictions of its future.

Kurth (Political Science Emeritus /Swarthmore Coll.; Family and Civilization, 2008, etc.) notes that the general consensus in the international community is that “we are now nearing a major inflection point in world history”—one marked by the nearly certain end of the “American Empire” and the diminishment of its global influence. The height of the United States’ power, he says, will be from 1945 to 2020—the “American Century”—within which the nation managed to rebuild Europe after its victory in World War II and successfully defeat the Soviet Union in the Cold War. With dizzying scholarly breadth, the author traces the development of America’s foreign policy from its inception, marking the birth of its imperial stature in the late 19th century—specifically, the Spanish-American War and aggressive expansion into Latin America and the Caribbean. Kurth explores the nation’s cultural and ideological traditions in his search for the nation’s identity—one that abides, despite oscillations in ideology between liberalism, conservatism, and socialism—and argues that Protestantism, as practiced by Americans, shows moral deterioration, due to “successive departures” from its original version. One could reasonably criticize the book for attempting to traverse too broad an intellectual landscape. Still, this is a compellingly astute study, and a brilliant indictment of the “extraordinary ambition, pride, greed, and fantasies” that left American influence “in ruins.” Over the course of this book, Kurth’s analysis is astonishingly exhaustive; he impressively covers the failings of the Iraq War, as well as the dangers of plutocracy, and he presents a conclusion that’s neither fatalistically grim nor cheerily hopeful: The United States will surely lose its worldwide dominance, he asserts, but not necessarily its prominence, and it will continue to persuasively offer the “most attractive…of the ways of life.” In order to do this, he says, it needs to maintain its technological superiority and recapture its economic strength.

A stunningly original work that provocatively explores the heights and depths of America’s global stature.

BookLife Review (11/23/19):

In this impressive and accessible work of scholarship, Kurth, professor emeritus of political science at Swarthmore, collects enlightening essays arguing that historic empire-building decisions—both successful and disastrous—shaped American foreign policy from the Revolutionary War to the present day. A theoretical overview of imperialist structures prepares the reader for analysis demonstrating how Protestant religious belief created an “American creed.” Kurth then explicates past military strategies and geopolitical events, examines how current strategies may enhance or impede the U.S.’s ability to accomplish its foreign policy goals, and thoughtfully extrapolates into the future. He makes connections that even dedicated readers of history will find both illuminating and applicable to current events.

The meticulously organized text and periodic references to previous talking points help the reader follow Kurth’s lines of reasoning. Readers new to the academic study of world events can easily parse Kurth’s ideas with the help of his strongly articulated theoretical framework. Kurth writes that the year 2001 ushered in “a long and trying period of descent and disintegration” from the peak of the triumph of the U.S. and its allies over Soviet Russia, and now sees that alliance system fracturing, heading toward “impending breakdown” both within the individual countries and in their alliances. The questions he then explores are what will replace this geopolitical system, and how the declining powers of the “Free World” will influence their successors. His essays provide an exceptional grounding in the whys and wherefores of American actions in relation to major powers such as Russia and China.

General readers will find some aspects difficult. Because the chapters were originally separate articles, primary concepts such as “the American way of war” are revisited in detail, which is an advantage for someone dipping into the book on different occasions but could prove irksome for some reading it straight through. The absence of maps is a challenge to readers interested in historical changes in boundary lines and areas of hegemonic influence. While not strictly necessary, such maps would be a bonus, particularly for a wider audience. Considered in terms of its arguments, however, this book has few flaws, and it would be a splendid gift for anyone seeking an in-depth look at the causes of current world tensions.

Takeaway: This deep dive into American imperial urges and their consequences will enlighten anyone interested in historical or present-day geopolitics.

Great for fans of Andrew Bacevich, Alfred McCoy.

"When it comes to deciphering the mysteries of American statecraft, no one can hold a candle to James Kurth. The American Way of Empire is, therefore, cause for gratitude and great rejoicing."

—Andrew J. Bacevich, author of The Age of Illusions

James Kurth is Claude C. Smith Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Swarthmore College. A Stanford graduate who received his doctorate under Harvard’s Samuel P. Huntington, he has published over 120 articles and edited Orbis: A Journal of International Relations, as well as two books. He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. A decorated Navy veteran, he taught strategy at the U.S. Naval War College, was advisor to the Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group, and has been awarded the Department of the Navy Medal for Meritorious Civilian Service. A world-traveler who has visited more than 50 countries, he serves as an elder at Proclamation Presbyterian Church in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

News about James Kurth's THE AMERICAN WAY OF EMPIRE

There's much to see here. So, take your time, look around, and learn all there is to know about us. We hope you enjoy our site and take a moment to drop us a line

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.

Elihyo Matz's AUSCHWITZ ON THE POTOMAC: Hillel Kook, the Attempt to Save European Jewry, and the Birth of the Israeli Nation